Resilience and Achievement in Filipino Diaspora in the U.S.

Filipina worker Anne Madriaga was bustling with activity at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, California, as she prepared for a new group of visitors lined up to board a vessel from the Red and White Fleet for the Golden Gate Bay Cruise.

It was a vibrant scene just before five in the afternoon in April at Pier 43 1/2, reflecting the bustling atmosphere typical of a United States coastal location. The area echoed with seagull calls, lively tourist chatter, and a blend of sea breeze and the enticing aroma of fresh seafood from nearby stalls.

The vibe was certainly one of excitement and anticipation, as people eagerly await their adventures on the bay, whether it’s a leisurely cruise, a visit to Alcatraz, or simply enjoying the stunning views of the Golden Gate Bridge.

Madriaga shared that the most fulfilling aspect of her job, despite initial skepticism from her male colleagues about her capabilities, is the opportunity to connect with people. When they discover she is Filipino, they often inquire about her homeland.

“At first, I faced many struggles and heard my male colleagues saying I couldn’t handle dock work—it’s a man’s job. They handle ropes, jump onto the pier as the ship approaches. But I told myself I would prove them wrong. As Filipinos, resilience is in our culture. I persevered, and now I work here regularly,” she said.

Her and her colleagues’ most difficult moments at the Red and White Fleet involved passengers attempting to jump from their ship or the Golden Gate Bridge and requiring immediate rescue. Madriaga hasn’t encountered this firsthand, but she has been trained to perform life-saving interventions when called upon.

Sean Cabiguen, who has been working in New York for 13 years, pursued his Doctorate in Nursing Practice after completing his Master of Science in Nursing.

Nursing practitioners (NPs) such as him take on advanced clinical roles, including diagnosing illnesses, prescribing medications, and managing patient care independently, whereas registered nurses (RNs) typically focus on direct patient care under the supervision of doctors and NPs.

“We are board-certified and licensed as advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs). The law here grants us the authority to diagnose patients, prescribe treatments, and order tests—it’s almost like being doctors ourselves.,” Cabiguen said as he walked us to Hell’s Kitchen in April.

There are significant differences between nurses in the Philippines and those in the US, not only in terms of clinical responsibilities but also in their cultural approach to healthcare delivery and patient interaction. Cabiguen said that back home, nurses often adapt to a healthcare system where familial involvement in patient care is common, whereas in the US, nurses might focus more on patient autonomy and individual decision-making in healthcare choices.

Cabiguen specializes in HIV treatment as a primary care provider, having worked previously as the nurse manager at the AIDS Healthcare Foundation in Chelsea, Manhattan, before advancing to become a NP. He also holds degrees in Business Administration and Nursing, an Advanced Diploma in Clinical Documentation Improvement, and a Master of Business Administration (MBA).

Jay Loyola left the Philippines 17 years ago as a male but now identifies as Sydney Loyola, having transitioned “to live authentically” as a woman. Upon arriving in the US, she began teaching at the American Center of Philippine Arts, a non-profit organization based in Oakland, California, specializing in traditional and contemporary Filipino dance forms.

The B.S. Tourism graduate was also hired as an adjunct professor at the University of San Francisco, where she started the Philippine Dance and Culture program in 2012.

“Actually, what really grounded me in this city and in the States is dance. It has been my guiding track. I never went out of that dance track. So, all of my opportunities came from my dance,” Loyola, who now works as a property manager in San Francisco, Loyola said.

However, for Loyola, the meaning of being in the United States extends beyond simply holding down a job to sustain herself and her family; it is the chance it afforded her to explore her true nature. In 2015, she started contemplating the idea of undergoing a gender shift in order to adopt a female identity.

Navigating these hurdles requires navigating both personal and societal barriers, including the emotional and practical challenges of identity exploration, healthcare, and legal processes associated with transitioning.

Loyola overcame these challenges by relying on her internal strength, supported by her loved ones, communities, and advocacy groups. Furthermore, she has access to affirming healthcare services and legal protections that promoted public acceptance as well as empathy.

“I thought, you know, I have already fulfilled whatever for my mom. I think I will do something for myself. My deal with my family was, this is me. If you don’t accept, I’ll deal with it. This country is a blessing because it gave me that chance to find my personal authenticity,” Loyola said.

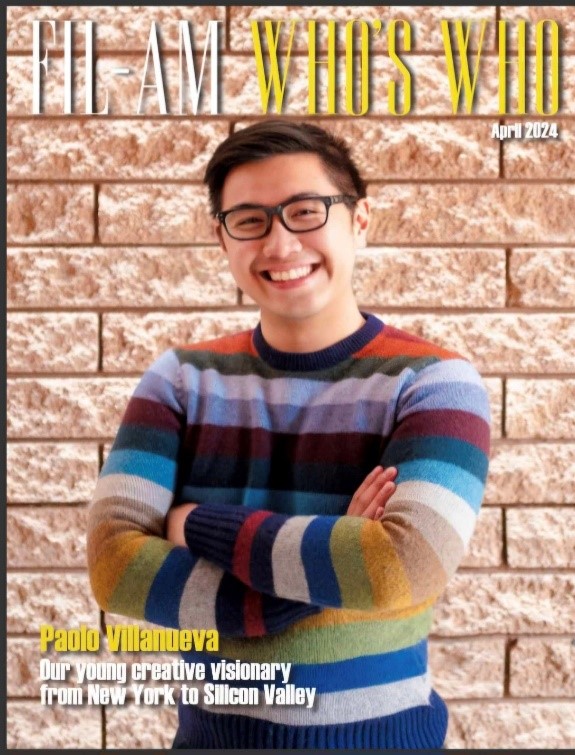

Virtual realist Paolo Villanueva, who hails from Butuan City and has worked at Ateneo de Davao University, is a technology creative now based in California. Originally from New York, he serves as the creative director at Heizenrader, a Utah-based company, and also in Silicon Valley in San Francisco, California.

Villanueva played a pivotal role in developing EducationXR. This platform is at the forefront of transforming educational paradigms, crafting Virtual Reality (VR) training and learning experiences tailored for medical institutions across the US. He helped these institutions and technical colleges to create their own learning experiences without the need for coding.

“Mostly with hospitals like national hospital, children’s hospital in Philadelphia, University of Nebraska Medical Center, folks like the CDC and many more medical device manufacture such as GE, Philips, Siemens to create immersive trainings for them that you can actually experience on your phone or VR headset,” Villanueva said.

Because of their talent, creativity, dedication and passion, Villanueva expects Filipinos to continue making significant contributions to the global technology scene.

“[Filipinos] They’re everywhere, and the thing that makes it cool is, they just don’t stand out, like someone who has done ordinary. They’re there. I’ve meet venture capitalist who are Filipinos, I’ve met folks in the engineering space, I’ve met folks who run the very amazing Apple keynotes for Filipinos, so they’re not essentially folks who stand out and say like, hey, I’m Filipino. Filipino is my identity, I work and I make and sell great things with the stuff here in Silicon Valley. I make the cool things for tomorrow, what we use,” he proudly says.

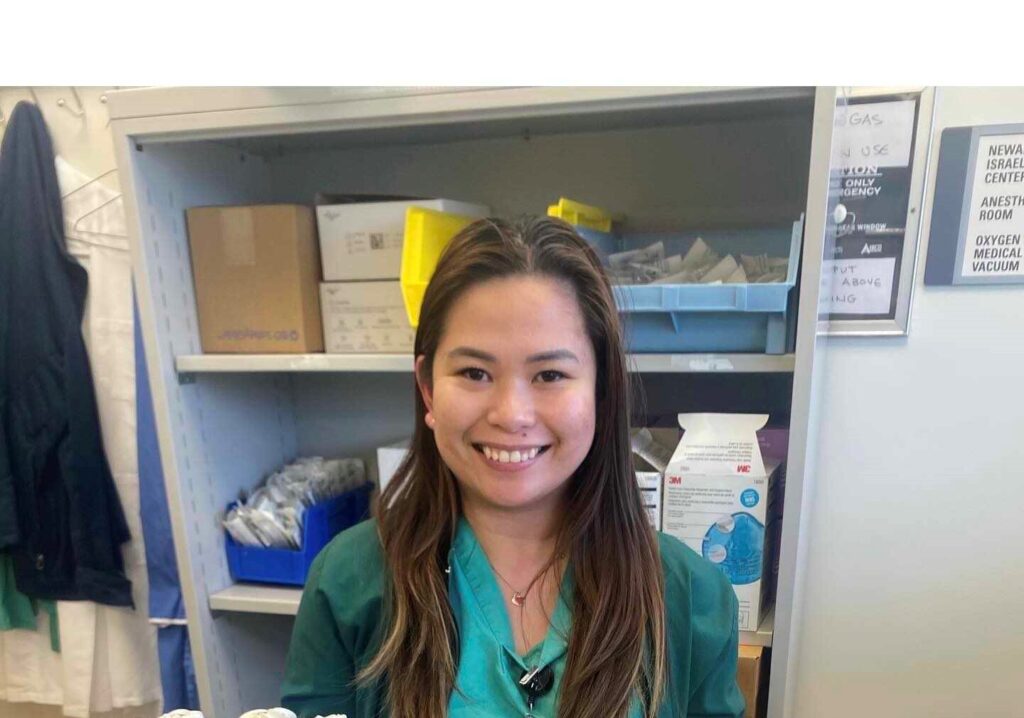

Jianzel ‘Jia’ Villacorte-Osdana, a Mass Communication graduate from Davao City, works as a full-time nurse at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, which focuses on oncology patients in Manhattan, New York, and as a part-time nurse in New Jersey.

She graduated in nursing from New York University in May 2020. As one of the thousands of Filipino nurses working in the United States, she exemplifies the love and care that are a trademark of Filipinos, especially when tending to her patients.

“With the Filipinos who came in here, I think they were still able to bring the Filipino values like in nursing, how they care for people, how they respect people, it’s still different,” Osdana said.

Why, among all the countries in the world, did they choose the US? And what can they say about Filipinos in the US?

“(The) US brought a lot of opportunities not only for me but I think with a lot of Filipinos especially with my field in nursing. I was able to meet people who were brought by the US during the moving of nursing,” says Osdana.

Madriaga, Cabiguen, Loyola, Villanueva and Osdana exemplify the many individuals who have migrated to the US and are making significant contributions to their fields. Their tales illuminate the roles and adventures of Filipinos in the Philippine diaspora, exhibiting their tenacity, adaptability, and professional accomplishments in many areas overseas.

The Filipino diaspora in the US stands as an integral and vibrant component of the country’s cultural fabric, embodying narratives of resilience, success, and unique cultural identities. This collective impact resonates through the personal stories of Filipinos and Filipino-Americans (Fil-Ams), who navigate challenges while embracing opportunities that the country offers, making it a favored destination for work and residence.

Filipinos began immigrating to the US in the late 1900s. The initial substantial influx occurred, predominantly in the form of workers employed in agriculture, fishery, and canneries. Referred to as the “Manong Generation,” these initial migrants, many from Ilocos, established themselves in Hawaii and the West Coast, braving difficult circumstances and racial prejudice.

Shelly Carmona, a Fil-Am from the Filipino Community Center, underlined that Filipino immigrants were pioneers in Hawaii’s plantation industry, working on sugarcane and pineapple plantations. This legacy is commemorated on Sakada Day, honoring their contribution as migrant laborers in agriculture.

“It’s a day that we take to commemorate the original migration from the Philippines to Hawaii. They’re the first plantation workers. They came here to work on agriculture because we had a lot of sugarcane and a lot of pineapple fields. There no longer is any sugarcane factories here. The last one closed a few years ago in Maui. But they were the original workers a long, long time ago,” she said.

After World War II, an increasing number of Filipinos joined the US military, which facilitated their acquisition of US citizenship. Subsequently, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which eliminated nationality-based restrictions, triggered a substantial surge in Filipino migration. Many were drawn to opportunities in sectors such as healthcare, engineering, and other professions.

As of 2021, according to the US Census Bureau and various sources, there were 4.1 million Filipinos and Filipino-Americans in the US, a number that grew to 4.4 million by 2023. Despite slight variations in exact counts, they constitute the third-largest Asian-American community, following Chinese and Indian-Americans. California, Hawaii, Texas, Nevada, and New York boast the highest concentrations of Filipino residents.

California alone is home to over 1.6 million Filipinos, with significant communities in cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego. In Hawaii, Filipinos make up nearly 25% of the population, reflecting their deep-rooted presence and influence in the state.

The Fil-Am community has achieved major strides in diverse professional domains. Within the healthcare sector, Filipino nurses constitute a considerable portion of the labor force, which serves as evidence of the community’s strong focus on education and dedication to providing service. The National Nurses United reports that almost 20% of internationally educated nurses in the US are from the Philippines.

ACROSS OCEANS

Emilyn Bayna, a registered nurse employed at Raleigh General Hospital in Beckley, West Virginia, characterized the United States as a challenging country to gain entry into. But Filipino immigrants successfully integrate into American society, they discover a multitude of opportunities that were previously unavailable to them in the Philippines.

Bayna moved to the United States under the EB3 visa category, part of the U.S. employment-based green card system. This category is tailored for foreign workers with skills, experience, or education desired by US employers, facilitating their immigration and permanent residency based on employment qualifications.

It’s difficult to go through the EB3 visa process because it has quotas and requires a lot of documents, according to Bayna. It is subject to annual numerical limits, which can cause delays in visa availability depending on the country of origin and demand.

“Some countries can face longer wait times due to high demand for visas,” she said.

“But although I faced challenges—as in it wasn’t really easy—I am here now. It can be challenging yet rewarding. Once you’re here and has adapted, you’ll be motivated to grow and advance professionally in ways that are not accessible back home. There’s also greater career stability available here,” she said.

Beyond healthcare, Fil-Ams have excelled in technology, engineering, business, and the arts. Notable figures include Grammy-winning musicians Bruno Mars and Allan Pineda Lindo (apl.de.ap) of the Black Eyed Peas, Enrique Iglesias, Olivia Rodrigo and Saweetie. Their achievements accentuate the diverse talents and contributions of Fil-Ams to the nation’s socio-economic fabric.

PEOPE-TO-PEOPLE EXCHANGE

The Philippines and the US have had a relationship for 75 years as friends, partners, and allies as they aim to strengthen democracy and development cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region. How has the US influenced the Philippines, and how has the Philippines influenced the US?

In 1910, American teachers introduced basketball to the public school system in the Philippines. Because it became popular, the Philippine Men’s Basketball Team, or Gilas Pilipinas, was established. Fil-Am players continue playing a significant role in the National Basketball Association (NBA).

In 1948, the Philippine-American Educational Foundation (PAEF) was established to run the Fulbright Program in the Philippines. The Binational Fulbright Commission in the Philippines is the oldest in the world and continues to this day.

In politics, there are Fil-Am leaders representing public office at the federal, state, and local levels. Sixty-six percent of Fil-Am public servants are in California, the state with the largest Filipino-American population. Notable leaders include Daly City Mayor Juslyn Manalo.

One of the most famous politicians in the US with Filipino heritage is Bobby Scott, the 3rd District Representative of Virginia. With a tenure spanning 30 years, he is the longest-serving Fil-Am in the House of Representatives.

Because of the deep relationship between the US and the Philippines, the two countries have 65 sister city relationships.

Currently, there are also about 350,000 US citizens living in the Philippines.

FOOD

Being a colony of the US for several decades, both the Philippines and the US have shared close cultural ties. This bond on culture manifests on different ways: Filipinos being so adept in the English language, the Philippines adapting US school system, and more interestingly, our shared ties in terms of culinary delights.

In the Philippines, malls have been dominated by American fast food and restaurants. For example, it’s not uncommon for one to see New York style pizza in public places in Manila and other urban places. Many restaurants serve American cuisine that it has been intertwined in the typical Filipino diet: burgers, fried chicken, to name a few.

In the US, where cuisine is vastly more diverse owing to its equally diverse population, we’re glad to see that Filipino food found its spots.

In Washington DC, a restaurant named Purple Patch gives Filipinos a taste of home. Owned by Filipino-Irish Patrice Cleary, Purple Patch serves traditional Filipino food, sometimes in fusion with global cuisine. It has the common pork dishes such as adobo and Filipino favorites like sinigang (various types of protein usually in tamarind soup).

Surprisingly, the food-savvy crowd of Purple Patch isn’t dominated by Filipinos. Americans and other nationalities also flock to Purple Patch to have their fix of Filipino delicacies.

Meanwhile, in Little Manila in New York City, primarily located in the Woodside neighborhood of Queens, there is a thriving community known for its Filipino restaurants, stores, and cultural events. Tito Rad’s Grill, described by the New York Times as a “foothold” for Philippine cuisine, can be found here.

One of its best sellers is the inihaw na panga (grilled tuna jaw), but regular customers like Edgar and Agnes Sinque would also highly recommend non-Filipinos try ukoy (bean sprout fritters), palabok (steamed rice noodles with shrimp sauce), adobo (pork meat braised in soy sauce, vinegar, and garlic), and dinuguan (pork stewed in vinegar and pork blood).

“Whenever we bring friends her who are not Filipinos, we recommend them. They love the taste of palabok, and also the halo-halo here at Tito Rad’s. Our favorite here is the ukoy and palabok, but every food here is recommendable,” Agnes, who works in New York, said.

She believes that Filipino food has now entered the mainstream of popular world cuisines, especially adobo, which many Americans truly enjoy.

Americans love adobo for its rich and savory flavors that come from the combination of soy sauce, vinegar, garlic, and spices used in the marinade. The dish offers a unique blend of tanginess and umami that appeals to many palates. Agnes said its versatility allows for variations with different meats (commonly pork or chicken) or even vegetables, making it adaptable to different preferences and dietary needs.

Adobo’s simplicity in preparation, hearty taste, and cultural significance as a staple dish in Filipino cuisine also contribute to its popularity among Americans seeking diverse and flavorful culinary experiences.

Aside from serving Filipino cuisine, spots like Purple Patch and Tito Rad’s become centers where the Filipino communities in the US can meet, convene, interact, and foster ties with fellow Filipinos. They provide safe spaces for Filipino migrants in the US, a recluse especially when they feel homesick.

CULTURAL PRESERVATION

Despite their success, Fil-Ams remain deeply connected to their cultural roots. Festivals such as the Philippine Independence Day Parade in New York and the Pistahan Parade and Festival in San Francisco celebrate Filipino heritage through music, dance, food, and traditional attire.

Organizations like the National Federation of Filipino American Associations (NaFFAA) play an important role in advocating for the community’s interests and fostering unity among Filipinos across the United States.

The Filipino Community Center (FilCom) in Waipahu, Hawaii, is a three-storey establishment on a 50,000-square-foot land that serves as an energetic platform for promoting Philippine culture.

On May 4, Filipinos gathered in this largest Fil-Com Center outside the US mainland for the Flores de Mayo and Filipino Fiesta, two events that display their passion for promoting their country’s culture and traditions.

The Santacruzan, a significant part of Filipino religious cultural heritage, was a standout feature of the Flores de Mayo and fiesta celebration. In Hawaii, the Filipino community held its own version of the Santacruzan at the Fil-Com Center last May 4, featuring Filipino-American youth who have long wanted to get in touch with their roots.

The Filipino community, partnering with the Filipino Jaycees of Honolulu, presented young Filipinos aged 5 to 17 depicting different representations of the Virgin Mary. The event culminated with the portrayal of Reyna Elena (Queen Helena), mother of Constantine the Great, who is revered for her discovery of the Holy Cross.

Similarly, the Flores de Mayo is also a May event that honors the Virgin Mary through floral offerings. Here, girls are given titles such as Reyna delas Flores (Queen of Flowers), Reyna Paz (Queen of Peace), and Reyna de la Justicia (Queen of Justice).

There were tweaks in the program, like the addition of Reyna Hawaii (Queen of Hawaii).

These events help Filipinos keep in touch with their cultural practices, especially for children who might have not grown up seeing this being done on their own homes.

Traditions evolve, sometimes adapted to new settings. Santacruzan in Hawaii is a proof that for Filipino migrants, home is not a geographic place. It’s them bringing their Filipino culture and beliefs to wherever life takes them.

The Flores de Mayo is an integral manifestation of Filipino identity, spirituality, and community cohesion, therefore holding a revered and essential role in Filipino cultural legacy.

Consul General of the Philippines Emil Fernandez pointed out that beyond promoting Filipino culture and traditions, the event served as a “great way to foster camaraderie and mutual support” within the Philippine diaspora.

“Events like this unify the community; they bring us closer together with the common goal of promoting our interests and contributing to the development of the Philippines back home,” Fernandez stated.

CHALLENGES IN THE DIASPORA

While the Filipino diaspora in the US continues to grow, many within the community, especially young Filipinos raised in American environments yet with Filipino heritage, face challenges in establishing a deep connection with their cultural roots.

This was true for Regine Victoria, a young Filipino professional in Arlington, Virginia. Victoria was born to Filipino parents; her father enlisted in the US Navy in the 1980s and was stationed first in San Diego, and later in Japan, where she was born.

Growing up in the US, she admitted that her limited knowledge of her culture and heritage occasionally made her feel like an “outsider” within the Filipino community.

“Most of my life until this year, I’ve never been a part of or felt comfortable with the Filipino-American community,” she shared. “I feel like [I’m] too American to be Filipino and too Filipino to be American.”

Victoria always struggled feeling “not good enough” to be called Filipino for not knowing the language and the Philippines’ history.

“I don’t know the language. I don’t know our history. I don’t know our culture. I know some of our foods, but none of that really makes you Filipino,” she said. To her, being Filipino is if a stranger comes up and asks about her culture and heritage, she would be able to teach them something.

It was only recently that she started actively participating in community activities after becoming part of the Filipino Young Professionals-Washington, D.C. chapter. She mentioned that this experience has somewhat helped her understand herself better.

For her, joining and creating similar organizations would also help Filipino-Americans like her, who ‘don’t feel like they belong to their own culture,’ secure that sense of belonging as Filipinos living overseas.

“I have to see someone who’s like me, who was really like drawn off. Because I know if someone who can have strong feelings about not belonging can actually join then maybe I can too,” she shared.

The struggles and successes of migration are vividly illustrated by the stories of Filipino immigrants who have made contributions to American society and who are actively shaping their local communities.

The rich fabric of Filipino-American legacy is enhanced with each passing generation, from the early pioneers of Hawaii’s plantations to the present-day healthcare professionals, artists, cultural champions, and others.

They demonstrate that, despite physical boundaries isolating them from their birthplace, their cultural heritage and values endure, generating relationships that span countries and enhance societies.

Written by Celeste Anna Formoso (Palawan News), Vinafel Pilapil (People’s Television Network), Jervis Manahan (ABS-CBN News), & Joyce Ann Rocamora (Philippine News Agency), and edited by Lucky Malicay (The Freeman)